Russian Realism vs Socialist Realism

I was recently speaking with a woman who remarked how much she loved Russian paintings because the people in them always looked so happy. It was an interesting comment because the paintings we love here at the Lazare Gallery—the masterpieces of Russian Realism that form the heart of our collection—tell a much different story. They are filled with profound depth and emotion, yes, but not always with smiles.

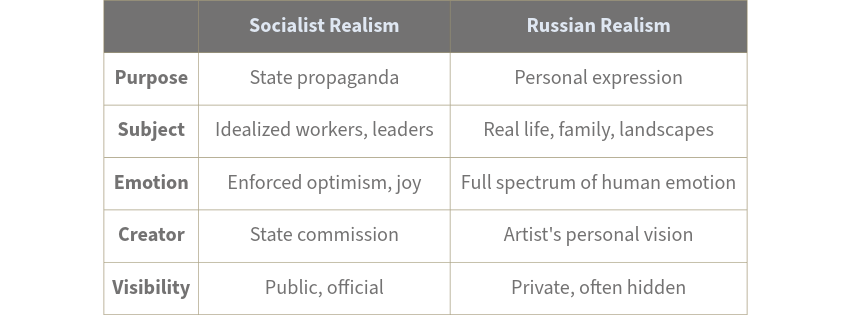

There is, however, a genre of Russian painting that does tell that bright, cheerful story, full of muscular workers, smiling farmers, and “wise” leaders gazing toward a glorious future. What the woman was referring to was Socialist Realism, the state-mandated art that glorified the nation and its laborers.

It’s the version of Russian art most people in the West recognize. Ask nine out of ten Americans to name a Russian art style, and they’ll likely say, “Socialist Realism”. But the world of Russian fine art is so much deeper, with a history far more complex and compelling.

As John Wurdeman—son of our curators and himself a Surikov-trained artist—puts it, “Socialist Realism was about propaganda and influence, while Russian Realism was simply about painting from the heart.” To truly appreciate the art of 20th-century Russia, we must look past the grand political statements and discover the intimate, heartfelt masterpieces created in the quiet of an artist’s studio—sometimes in secret, hidden from the watchful eyes of an unforgiving authoritarian regime.

Key Takeaways

Two Distinct Genres: Most Westerners are familiar with Socialist Realism, the state-mandated propaganda art of the Soviet Union. However, another profound genre, Russian Realism, focused on personal, emotional, and authentic depictions of life, often created in secret.

Art as a State Tool: Socialist Realism was officially decreed in 1934 to serve the Communist Party. It glorified idealized workers, happy farmers, and a perfect future, using a realistic style that was easy for the masses to understand.

The Survival of Technique: Ironically, Stalin's regime preserved classical art training by reinstating 19th-century art academies. This ensured that artists maintained high-level technical skills in drawing and painting, which were often abandoned for modernism in the West.

A "Double Life" for Artists: Many of Russia's most talented artists fulfilled their government commissions for Socialist Realist works while privately creating personal, apolitical art that captured the true human condition.

Discovery After the Iron Curtain: It wasn't until the era of Glasnost and the fall of the Soviet Union that this hidden world of authentic Russian Realism was revealed to Western collectors, showcasing an unbroken lineage of master-level skill.

The Art of the State: Socialist Realism

Early in its history, the Soviet Union embraced the bold banners and angular designs of the avant-garde, replacing the strong tradition of realism inherited from 19th century Russian painters. But Stalin saw this modern, abstract art as elitist, believing ordinary people couldn’t connect with it. His logic, likely influenced by his early seminary education, was coldly pragmatic: if the state wanted to influence the masses, it needed an art that was as direct and understandable as the frescoes in medieval churches were to an illiterate congregation.

And so, in 1934, Socialist Realism became law. Art was now officially a tool of the state. Its core tenets were clear: art had to be proletarian (relevant to the worker), typical (depicting idealized scenes of everyday life), realistic (nothing fantastical), and partisan (unwaveringly supportive of the Party's goals). As John Wurdeman describes it, you saw paintings of "women with big biceps exuberantly happy to be on a tractor going out to the fields to collect cabbage" or "men that were joyously working in the coal mines". The message was always more important than the medium; the content more critical than the form.

The Quiet Survival of Truth

The Russia of the 20th century became a land of two worlds, not unlike the Orwellian state of "doublethink". We mentioned in our last article that gathering the Lazare collection felt like a clandestine affair; but for the artists themselves, true artistic expression was a clandestine affair.

In a strange twist of fate, it was Stalin who ensured the survival of classical technique. He reinstated the great 19th-century art academies, like the Surikov Institute in Moscow and the Repin Academy in St. Petersburg. This act preserved a deep, foundational knowledge of drawing, painting from life, and interpreting the visible world—skills that were being abandoned in the West in favor of modernism.

A bizarre and unspoken arrangement emerged. The most brilliant graduates of the Surikov were given a strange kind of freedom. While many fulfilled their quota of government commissions, they were allowed to continue their own private work, as long as it remained quiet. They could paint scenes from their lives, portraits of their families, and the landscapes they loved, but the art had to contain no politics, no protest—only beauty and the human condition.

Glasnost and a World Revealed

The heavy hand of the state didn't truly begin to lift until Gorbachev's era of Glasnost ("openness"), which made it nearly impossible for authorities to continue placing restrictions on artists. This was a huge shift from the decades before, when artists who strayed too far from the official line faced imprisonment in Siberian labor camps, their life's work sometimes destroyed by bulldozers.

With this new dawn, a gallery system began to form, freeing artists from their reliance on the state. They could finally create for themselves and for a new class of private patrons, bringing their heartfelt work out of the studio and into the light.

Alexandriech Fomkin's "Summer", an example of Russian Realism

But it wasn't until after the fall of the Iron Curtain that collectors in the West began to discover the astonishing quality of the realist art produced during those years. For us, that moment came after we held an exhibition in New York for our son, John, and his friends from the Surikov Institute. The collectors there were stunned.

The Surikov is still recognized as the strongest school of realism in existence. The core principles of the tradition persisted through decades of immense pressure, ready to flourish once again when the barriers came down. It is this unbroken lineage of skill, passion, and quiet courage that we are honored to share with you today at our gallery. We invite you to come and take home one of these historic masterpieces to adorn your walls today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What is the main difference between Russian Realism and Socialist Realism? A: The primary difference is intent. Socialist Realism was state-mandated propaganda designed to promote a political ideology. Russian Realism was personal, heartfelt art focused on genuine human emotion, beauty, and daily life, often created without political motives.

Q2: Why is Socialist Realism more famous in the West? A: Because it was the "official" art of the Soviet Union, it was the style most often exhibited, published, and seen by foreigners during the Cold War. The more personal Russian Realist works were largely hidden until after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Q3: Were artists in danger for painting in the Russian Realist style? A: Artists were in danger if their work was seen as critical of the state. As long as their private work was apolitical—focusing on landscapes, portraits, or still life—they were often left alone. However, creating and especially exhibiting art that defied the party line was a serious risk.