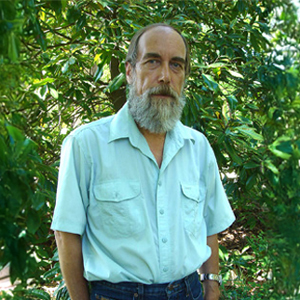

Nikolai Kozlov (b. 1947) is a prominent contemporary artist and a key member of the Moscow River School, a group known for its focus on capturing atmosphere and the spirit of the Russian landscape. His artistic education was extensive; after attending drawing courses at the Surikov Institute's preparatory school and serving in the army, he was accepted to the Art College of 1905 in Moscow. He later continued his studies in the painting department at the prestigious All Union Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in 1974. Since 1980, he has been a teacher at The Moscow Preparatory Art School, shaping a new generation of artists.

Kozlov is considered a "master of form, space, and spirit," and his paintings are celebrated for their exceptional ability to render a specific mood and atmosphere. This mastery is evident in the works from the Lazare Gallery collection. In his painting "June Breeze," he skillfully captures the intangible feeling of a gentle wind, likely through his nuanced depiction of light and movement in nature. In another piece, "Suburban Evening," he finds a deep, poetic beauty in a quiet, everyday scene, showcasing his expertise in conveying the transitional light and peaceful mood of twilight.

Nikolai Kozlov's work has been recognized internationally. In 2006, his paintings were featured in the 'Form, Space, & Feeling' exhibitions held across the United States in Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina. For the collector, a painting by Kozlov offers the opportunity to acquire a work by a contemporary master of the Moscow River School. His landscapes are not just depictions of a place, but are profound, atmospheric studies created by an artist praised for his mastery of form, space, and spirit.

April 2006, 'Form, Space, & Feeling', Charles City, VA, Longboat Key, FL, and Wilmington, NC

The Observer, Longboat Key, FL, 'Impressions and Expressions', Self Portrait