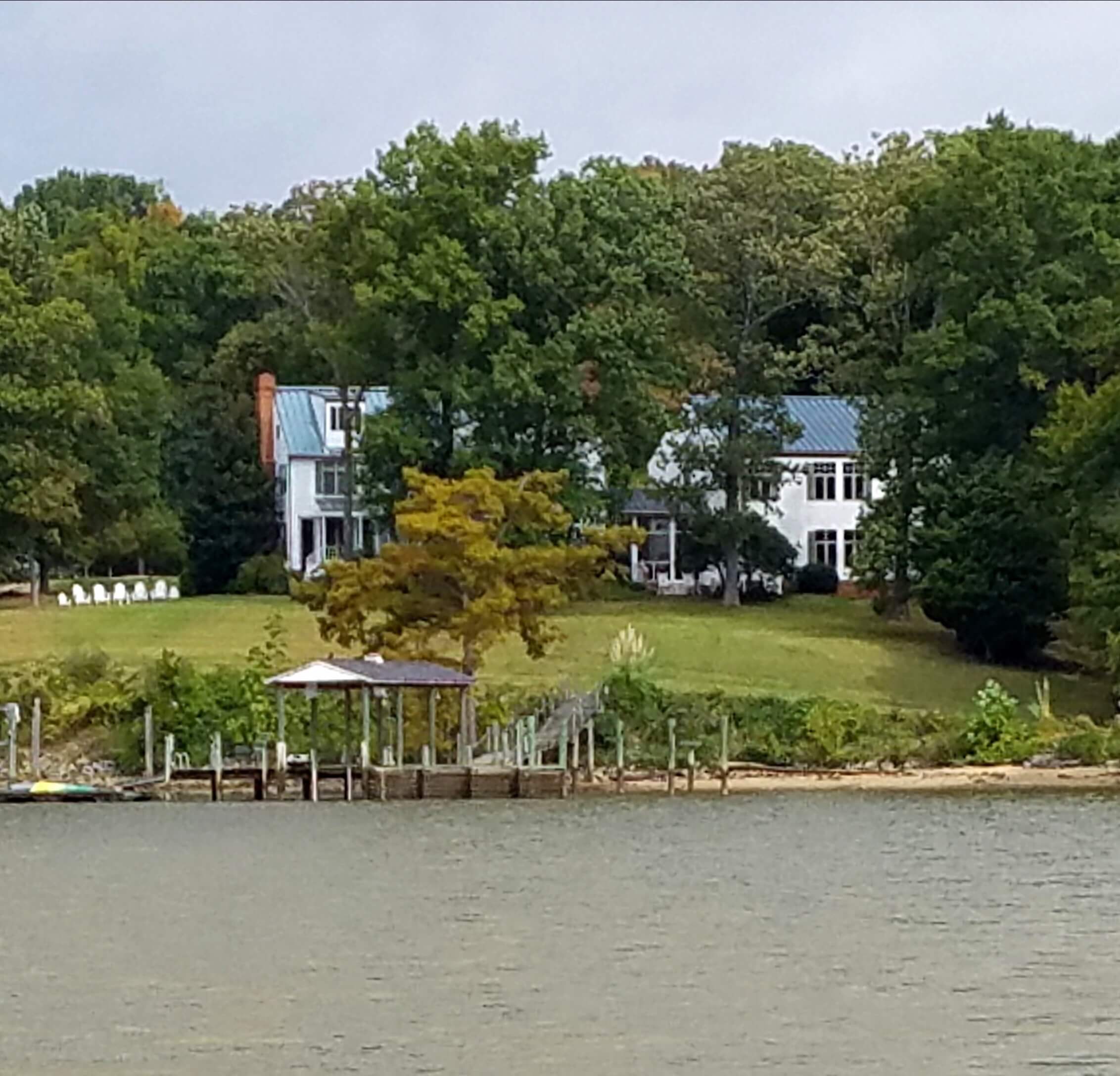

For Lazare, we set out to create more than a gallery. We wanted to create a true art destination that would be ideal to house our growing collection of Russian realist and impressionist masterpieces. We found this old historic home situated away from the distractions of major urban centers in Charles City County, Virginia, just upriver from Colonial Williamsburg. It offers an idyllic setting as timeless as the works we exhibit. Nestled along the banks of the James River, our 8,200-square-foot gallery evokes the spirit of pre-Revolutionary Russian patron estates, where 19th century Russian artists once found both inspiration and sanctuary.

We began in the art business in 1991 as a decorative print wholesaler, Old World Prints, and were in cooperation with several prestigious clients, like Waldorf Astoria hotels and Crate & Barrel. But when our own son, John, set off to the Surikov Institute to study composition, our entire world was about to change.

When we showed John’s paintings as part of an exhibit at the Art Expo in New York City in 1999, we knew we had found our niche: to run a gallery of our own. We visited John at the Surikov, which opened us up to another side of art. We thought we had understood art before, but meeting the master Vyacheslav Zabelin, we learned a whole new perspective on the relationship between colors and form.

We came back from Moscow with over 200 paintings. So many that the CIA thought were up to some secret plot. Though when they discovered we were just connoisseurs opening a new gallery, their interest subsided. Since then, we’ve gathered a collection of over 2,000 works of art, many by the highly trained and skilled Surikov Institute artists whom we met while visiting our son.

Prices for the pieces range from $1,000 to up to $1 million. We invite all collectors and those looking for a prized showpiece for their home or place of business to look through our collection, here online or at the gallery in Virginia. Tell us what you’re looking for and let us help you find your perfect piece. Don’t hesitate to get in touch!